The Changing Face of Government

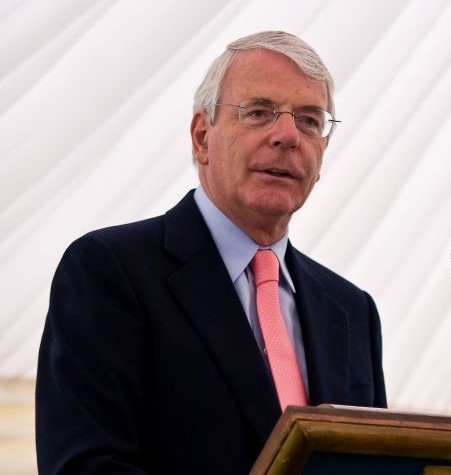

Delivered by

The Rt Hon Sir John Major, KG, CH

Sir John served as Chairman of the Council of Management of The Ditchley Foundation between 2000-2009. He is currently Joint President of Chatham House (2009-), which he combines with his business appointments as Senior Adviser to Credit Suisse; Chairman, European Advisory Board, Emerson Electric Company; Chairman, International Advisory Board, National Bank of Kuwait; Chairman, Advisory Board, Global Infrastructure Partners; Chairman, Global Advisory Board, AECOM. Sir John was the elected Member of Parliament for Huntingdon from 1979 until 2001, and was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1990-1997.

The changing face of government

First, let me add my welcome to Jeremy and Anne Greenstock and John and Penny Holmes.

Jeremy and Anne have been great servants of Ditchley; John and Penny are already showing they will be. We are lucky to have them.

When John invited me to speak to you today, I was very reluctant to accept. I was dismayed that, once again – with impeccably bad timing – the Ditchley Lecture clashes with a Test Match. I also recalled some outstanding Lectures at Ditchley over recent years. I nearly said – No.

I didn’t, because there are things to be said, questions to be asked – and ideas to be floated – that can more easily be done by a former politician than a current one. And where better than Ditchley – for so long a home for rational thought and considered debate? An oasis of calm in a world of frenzy.

Every time I come here I am reminded of our debt to David Wills – and now, Lady Wills and Catherine.

I just want to say to Eva and Catherine: we owe you more than we can repay.

In preparing for today, I took to heart GH Hardy’s observation that one ought never to waste time stating a majority opinion. I will try and follow that advice.

Accepted opinion is often wrong. Even more often, out of date. And, frequently, complacent.

Let me say at the outset that nothing I say should be taken as a trial balloon for anyone else. I speak for myself alone and – reluctantly but possibly – will offend political friend and foe alike. Nevertheless, I shall set out what I believe Western Governments must do to secure our well-being, in a world that is moving faster than we are.

This world is digitalising, urbanising and ageing. It is also migrating. The age of the single language, single culture state is over. Medicine, science and technology are carrying us where we have never been before. Social networks can elect Presidents and foment revolution. Global markets have outstripped the control of nation states.

The world of 20 years ago, let alone 50, has long since vanished. In every field of human endeavour – and nearly every aspect of life – yesterday’s certainties are today’s imponderables and tomorrow’s dilemmas.

The future raises uncomfortable questions, and even more uncomfortable answers. Some challenges are domestic, others can be resolved only by collective action. And, even if they are faced, and even if there are successful outcomes – and these are two big “ifs” – they will merely head off future problems.

Pain now for gain later has never been an easy sell for politicians and, in a social climate that expects instant gratification, it becomes even harder. It was easier being a politician yesterday than today. And it is easier today than it will be tomorrow.

The core question is: what must our Governments do to ensure our future prosperity? Must we change our policies, our expectations, our tribal politics – or all of these? It simply defies logic that the whole world can turn upside down, while we meander on in the same old way. At stake is our material well-being – and our status in the world – in 20, 40, and 50 years’ time.

Some may say the battle is lost – that this will be China’s – and Asia’s – Century. I don’t believe that is pre-ordained. China, in particular, has many problems. The Communist philosophy is discredited. Her Government is not elected. Its only legitimacy is growth.

In China and Asia, we are already seeing that rising living standards will bring greater demands – for social welfare, pension and much else besides – that will eat away at their present competitiveness.

So this economic triumph of the East isn’t assured, but we do know they will be formidable competitors. So how are we placed to respond?

Our present position, to put it mildly, is uncomfortable. It is axiomatic that every generation has an obligation to pass on to its successor something better than they themselves inherited. In recent times, we have failed.

We have spent tomorrow’s money on yesterday’s gratification, and there is something immoral in that. And we have presided over a systemic financial collapse that has forced the prudent to bail out the reckless. There is something unjust in that.

This is a sharp reminder that our democracy doesn’t guarantee efficiency. The democratic checks and balances we so cherish can become roadblocks. The tyranny of the electoral cycle can push politicians to short-term decisions.

Equality replaces quality. Sound-bites stand in for home truths. It feels odd to point up the short-comings of democracy, when it has achieved so much – but if we don’t recognise them, we can’t correct them.

Democracy has entrenched an enviable liberty of thought and action and presided over a quality of life our forebears could not have imagined. We are safer and, until now, richer. It has had a civilising influence. We have learned that decent people come in all colours. We abhor racism and bigotry. We have developed good human instincts of care and compassion.

In due time, electors can vote Governments out and mostly they depart peacefully into Opposition. No wonder it is widely admired and copied. It has served us well but, on its own, democracy will not secure our place in tomorrow’s world.

ECONOMY

The financial crisis has highlighted a reality the West can no longer ignore: our days of easy economic supremacy are over.

The drift is undeniable. The West has lost its competitive edge against China, India, Indonesia and Brazil as well as many smaller countries, notably in Asia and Latin America. Financial firepower is moving from West to East. Thirty five years ago, the fifteen core countries of the EU accounted for broadly 36% of global GDP, and Asia only 16%. Projections suggest that, in twenty years’ time, that will almost precisely have reversed. As we stutter, the rest of the world grows.

America has, largely, held decline at bay: but, even so, her share of global GDP has fallen from 26% to 23%. Economically, in one lifetime, the world will have turned on its head.

It’s easy to see why. Where ambition confronts complacency, ambition wins. In countries that are one generation away from poverty I see a passion and drive for success that sweeps away barriers. Even if we are aware of the tidal wave of competition that is coming, we have not prepared for it. We are falling behind and at risk of falling further.

We shouldn’t deceive ourselves this is simply the fall-out from the financial crisis. It is a long-term trend.

Some see no danger. They argue that the West can be sanguine about Eastern competitiveness because our quality of life is so far ahead. Such people should get out more. Let me cast an unforgiving eye on that complacency: the UK first.

In terms of GDP, the UK is the sixth most wealthy country in the world. But our national Balance Sheet carries many liabilities. Our physical infrastructure is old. Our health service is creaking. Whilst the best of our education – especially higher education – is world-class, some of it is unforgivably awful.

We are up to our ears in debt. The Exchequer is empty. The Gold is gone. The post-dated cheques are accumulating interest. We are over-taxed. We have an under-class: poorly educated, poorly housed and unmotivated.

We are no longer an Empire, nor will be ever again. Today, we are a shrinking military power. By choice, and with majority public approval, we are semi-detached members of the EU. And even America – for so long our closest ally who generally sees the world as we do – is turning her face to the East, as self-interest determines she must.

There is absolutely nothing here to be complacent about.

America faces many similar problems – most obviously debt, which was 40% of GDP in 2008, 69% in 2011, and is projected to be 85% by the end of the decade – and rising. Yet only about one-half of the population pays federal income taxes.

The risk remains of the US Treasury defaulting on its debt as it runs up against the legal limit it can borrow. I daresay a compromise will be reached, but this flirting with brinkmanship is dangerous. The collapse of Lehman Brothers was catastrophic. A Treasury default could be as bad. I hope those playing political games realise that the effect of their actions could spread far beyond America.

In the foremost free market economy in the world, average household debt comfortably exceeds average annual income. And a rising proportion of that income now comes from the State.

About 45 million Americans now receive food stamps: the modern equivalent of bread lines. Medical costs threaten to spiral out of control. Huge housing debts held by Banks are not written off: if they were, there would be lower profits, and lower bonuses. Total mortgage debt has quadrupled in 20 years. Today, there are two million mortgages not being paid.

And so the merry-go-round continues: Banks are still lending 95% mortgages on a falling market at a multiple of income: admittedly now – they say – only to more credit worthy customers. No‑one should assume the financial crisis cannot be repeated: it certainly can. But, if it is, it will be unforgiveable.

EUROPE

As for Europe – the word is engraved on my heart. Northern Europe is healthy but Southern Europe is sunk in debt and uncompetitive. The EU as a whole is divided on how to handle budget deficits, the crisis in the Eurozone, control of the Central Bank, nuclear policy, as well as how to react to Libya, Afghanistan and the Arab/Israeli conflict.

Twenty years ago, led by France and Germany, a confident EU was paving the way for the Euro. The assumption in the European Council was that, before the Euro could be launched, the economies of nations wishing to be part of it would converge: by that piece of jargon, we meant operate at broadly the same level of efficiency.

But that didn’t happen. It was politics – not economics – that launched the Euro in the late 1990s. Sterling did not join because, in 1992, I had opted out of the Euro at Maastricht. I didn’t do that out of sentimentality for the Pound – nor to placate sceptic opinion. If I’d wished to do that – with my Party or the Press – my life would have been much more comfortable. I didn’t. It wasn’t – because I thought then, and argued then, that the concept had flaws.

Today, Germany – with its powerhouse economy – is locked within the same currency, at the same exchange rate, as the weaker economies of the Southern European States.

In a sensible world, the Southern States would devalue but – of course – they can’t and so, to become competitive and stay in the Eurozone, they must devalue internally. Unemployment will rise, wages must fall, and so must living standards.

This threatens Greece, Portugal, and – possibly Spain and Ireland – with many years of austerity. As we see in Greece, the scale of that austerity may not be acceptable in a liberal democracy. Meanwhile, others power ahead.

It is not immediately clear how Europe will resolve this dilemma. But the present position is unsustainable. Either the EU becomes effectively a Union of transfer payments to offset regional disparities (as happens in Canada), or it creates a mechanism to shrink the Eurozone. Nothing else makes long-term sense.

Germany and France will not permit – cannot afford to permit – a reprise of the present crisis. In Germany, in particular, it is causing immense political agony. When the President of the ECB proposed a European Ministry of Finance with power to intervene in national economic policies, he caused commotion. But something will have to be done. Somehow, binding rules will be imposed on debtors.

Despite Eurozone members insisting they will not surrender fiscal sovereignty, it is not hard to look ahead and imagine a Eurozone with fiscal – as well as economic – union, in practice if not in name. I don’t like this – it was a prime reason for not joining the Euro – but, if it happens, it may have the effect of pushing the UK further away from the mainstream of the EU.

The UK is often accused of being half-hearted over its commitment to Europe. Continental politicians bemoan our caution. “If only the UK took up its responsibilities” ... it is a familiar theme, and we will hear more of it.

Let me respond. I am not anti-European. I am not a sceptic in the accepted sense. I never have been. I see the nobility of intent in binding together nations that fought one another over many centuries.

I see the economic advantages of the single market, and the political advantages of extending democracy to nations that were locked in the Soviet embrace. But I am wary of many European policies. If they are flawed, or unworkable, or alien to our instincts, our Government has a duty to question them.

Where we can work together, let us do so. That is sensible. But the Union cannot succeed if nations are – sullenly and resentfully – bound into policies they believe are damaging to their national interest. Far better to plan for a multi-speed Union, with nations opting-in to policy rather than opting-out. In a 27 Nation Union, I believe we will come to that, although it is far from the ambitions of some of our partners.

If the UK is semi-detached, that is only, in part, because of British scepticism: it is also because the EU has chosen, time and again, to go in a direction they know Britain cannot follow. Every recent Prime Minister has ended up less European than he – or she – began.

As to the future – it is difficult to see where Europe is going. Some would like to break away entirely from the EU. In a world in which many policies need collective action, that would be folly. If we are drifting apart, there is cause to beware: it is time to take stock.

GOVERNMENT/POLITICAL SYSTEM

In the search for future well-being that is true of our political system as well. At the moment, neither American nor British politics is in a state of grace. It has become too inward-looking. Too short-term. Our systems embrace politicians, and carry them off to a world the rest of us don’t inhabit. It’s time to bring them back. And focus them on the far distance as well as tomorrow.

There is a fault line in our national policy-making processes:

When do politicians have time to think?

There is time to do, based on advice.

There are policies to advocate, based on conviction.

There are people to placate, based on necessity.

But, in Government, too often, senior politicians are fire-fighting yesterday’s problems instead of thinking how to fore-stall tomorrow’s. Would it not be better to carve out sufficient time so that – routinely – they can frame policies to safeguard our future in 20/50 years from now?

And – if they did think and plan far ahead – it would give them time to explain, to cajole and to carry electorates with them in controversial policy. That’s never easy – as we see today.

To help bring this about, we should encourage governments to devolve more and do less: in some areas, we are ludicrously over-governed. The nanny state may be well-meaning, but it is also stifling.

I am one-quarter American, so I hope I might be forgiven for speaking bluntly. At the moment, the American political system is dysfunctional.

It is easier to stop good policy than to pass it. Bi-partisan co-operation is grudging and limited. Moreover, it is getting worse as re-warding of congress and district boundaries makes seats safer for Republicans or Democrats: the inevitable effect is fewer “middle of the road” candidates being elected. The first loser is compromise. The ultimate loser is sensible, non-ideological policy.

The power of special interest lobbies is excessive. There have been 27 Bills affecting Energy over recent years where the representatives of six States, irrespective of Party affiliation, have voted for the Coal lobby position on over 80% of votes. In the Senate, this has been sufficient to block anything the industry does not favour. This is not in the national interest. It is naked self-interest. Sadly, it is not the only example (in domestic or foreign policy).

I remember former Presidents bemoaning the introspection of Congress – my expression, not theirs – and their concern that only a minority of its Members travelled overseas to see the world for themselves. Since American foreign policy affects us all, this is lamentable.

But it’s easy to see why. A competitive election contest in New York, or New Jersey, home to the most expensive media markets, could cost a candidate $10 million. On average, candidates must raise over $1.3 million to fight each campaign. And campaigns come every other year.

To fight these elections, the average candidate must raise over $50,000 each and every month. No wonder they don’t travel. Such frequent elections also create obligations to donors – and lobbies. They put a premium on short-term populist policies.

It would make for far better decision-making if elections were less frequent and there were limits on spending. This might also cut down on negative campaign advertisements, the net effect of which is simply to damage the reputation of politics.

I claim no superiority for the British system.

For generations, Britain has basked in the glory of our Parliamentary system. Much of the world flatters it as an example of a mature democracy, a supreme Parliament, an independent Judiciary and an impartial civil service.

I cherish the traditions that add majesty to Parliament. Yet even I, who look at Parliament with affection, can see it must be made more efficient.

We could begin by widening the pool of talent prepared to enter politics, by removing some of the disincentives to do so.

I would pay MPs a fixed and generous salary, and cut out all living allowances. This is not entirely fair to Members with remote constituencies, but life is not fair – and such a system would avoid the recent scandals that have done so much harm to Parliament.

We need, also, to attract to the Commons men and women at the top of their profession. It is one of the oddities of democracy that fundamental policy choices are made by men and women who, apart from the legitimacy of election and a native intellect, have no qualifications to make them.

How many MPs can bring direct knowledge to how banks should be regulated? Or how hedge funds work? Or are familiar with e-money? Or nuclear energy? Or the social and medical implications of embryology?

We would benefit from our legislators having more practical knowledge.

Of course we can hire specialist advisers, but that can never be as effective as influential, knowledgeable voices speaking with expertise in the Chamber, in the Committees, in the tea rooms, in Party meetings.

There is no solution to this dilemma that doesn’t cut across our traditions, and so I would do just that. Why not elect fewer Members of Parliament and appoint, on a basis pro rata to votes cast in the General Election, a similar number of Members without constituencies?

I know the familiar arguments against this – a few years ago I would have used them myself forcibly – but, on reflection, I now believe enhancement of the talent pool is so vital it justifies the changes.

If the Commons baulks at a further reduction in its Members then, as Douglas Hurd and I have argued before, let us appoint unelected Ministers, answerable to Parliament, but without being Members of it. Or, of course, let us do both. Douglas and I have argued also for fewer Ministers and fewer PPSs: we have far too many of each: they could be severely cut back.

At the moment, all three major Parties are committed to an – at least partly – elected House of Lords. The Lords does need reform. It has too many inactive Members. It is too big and unwieldy. But election is the wrong reform.

The case for election is democratic legitimacy. However, if we want an efficient legislature, the case against is far more compelling.

An elected Upper House would cease to be a revising Chamber and would demand more powers that could only come from the Commons. There would be confusion and conflict. We should be reducing the number of politicians and adding to their quality. An elected Lords would add more politicians and reduce their quality. That is a bad bargain.

Does anyone imagine that Chiefs of the General Staff, Cabinet or Permanent Secretaries, Captains of Industry, Chancellors of Universities, Professors of Medicine would stand for election?

Of course they wouldn’t, and elected replacements could never bring such a depth of knowledge to the scrutiny of legislation. If the answer is more elected politicians, we are asking the wrong question.

A better reform would be to improve Parliamentary procedures. Cut the number of whipped votes. And reform PMQs to discourage its vaudeville element.

I offer only one further of many options. Parliament’s workload leads to legislation being poorly scrutinised, and often shown to be defective. In Criminal Justice alone, 68 sections and 25 schedules of 19 Acts remain unimplemented: many because they are unworkable.

Why not subject all mainstream Bills to Select Committee scrutiny and public evidence before final drafting? If we did so, we would get better, more relevant, and more coherent, new laws.

And must the Westminster Parliament oversee so much? I think not. It would be more efficient if it were less over-burdened.

DEVOLUTION OF POWER

There are options:

Pass fewer laws – which is attractive, and to be hoped for: though I’m not holding my breath.

But we could contract more to local government and devolve more to the Scottish, Welsh and Northern Ireland Assemblies. In a cautious and incremental way, the Coalition is taking action to do this. I welcome that and encourage them to go further.

Some years ago, I opposed the creation of local Mayors. I was wrong. Mayors do put in place a dynamic and – as successive Mayors of London have shown – they can be effective megaphones for our big cities. But under present plans, Mayors will only inherit the existing powers of Council leaders: in future, I hope their remit can be widened.

There is one caveat: their power of decision should be real, not illusory, and this implies a funding responsibility to pay for – at least the majority of – their policies. When next we look at local authority finance that should be the objective.

Devolution can also reduce the Westminster workload. But there is some groundwork to be cleared first. The present quasi-federalist settlement with Scotland is unsustainable. Each year of devolution has moved Scotland further from England. Scottish ambition is fraying English tolerance. This is a tie that will snap – unless the issue is resolved.

The Union between England and Scotland cannot be maintained by constant aggravation in Scotland and appeasement in London. I believe it is time to confront the argument head on.

I opposed Devolution because I am a Unionist. I believed it would be a stepping stone to Separation.

That danger still exists. Separatists are proud Scots who believe Scotland can govern itself: in this, they are surely right. So they point up grievances because their case thrives on discontent with the status quo. But even master magicians need props for their illusions: remove the props, and the illusion vanishes.

The props are grievances about power retained at Westminster. The present Scotland Bill does offer more power to the Scottish Parliament. But why not go further? Why not devolve all responsibilities except foreign policy, defence and management of the economy?

Why not let Scotland have wider tax-raising powers to pay for their policies and, in return, abolish the present block grant settlement, reduce Scottish representation in the Commons, and cut the legislative burden at Westminster?

My own view on Scottish independence is very straightforward: it would be folly – bad for Scotland and bad for England – but, if Scots insist on it, England cannot – and should not – deny them.

England is their partner in the Union, not their overlord. But Unionists have a responsibility to tell Scotland what independence entails.

A referendum in favour of separation is only the beginning. The terms must then be negotiated and a further referendum held.

These terms might deter many Scots. No Barnett Formula. No Block Grant. No more representation at Westminster. No automatic help with crises such as Royal Bank of Scotland. I daresay free prescriptions would end and tuition fees begin.

And there is no certainty of membership of the EU. Scotland would have to apply, meet tough criteria, await lengthy negotiations and would find countries like Spain – concerned at losing Catalonia – might not hold out a welcome for Separatists. And, even if Scotland were admitted, they would find their voice of 5 million is lost and powerless in a Union of 500 million.

But it must, ultimately, be their choice.

SOCIETY

Reforms within politics can – I believe would – improve policy-making, but it is the guts of policy that really matters. I simply observe that in considering future policy every Minister should ask one question: does this improve our long-term ability to compete and grow? If it does – good; if it doesn’t – think again.

Growth is not just a matter of economic policy. Social policy is a partof the competitive structure – not apartfrom it. To grow, we need to improve our human infrastructure.

EDUCATION

Education and skill attainment are as crucial to economic success as cash investment. In the ancient world, Plato taught Socrates who taught Alexander.

Rather more recently, Tony Blair famously declaimed “Education, Education, Education”. I had the same priorities but in a different order. Neither of us was original. Lenin first said it in 1917.

And we were all right – except that we failed. And among the alienated and the under-educated, how much talent is lost? How many lives are wasted and unfulfilled? How high is the social and economic loss? Money has been put into education but the return on investment has been disappointing.

It is a reproach to every Government over the last 40 years that employers routinely bemoan the numeracy and literacy of far too many school-leavers. As a Nation, we can’t afford that.

A recent OECD survey, based on science, maths and literacy, put America – once top – at 26th, and the UK even lower: eight of the top ten performers were emerging Asian States. This isn’t some remote trend we can ignore: our children and grandchildren will be in direct competition with these young Asians.

One reason for Asian success seems to be that they have invested heavily in teachers. Paid them well. Trained them well. And built up their prestige and social standing. As a result, they have attracted their brightest and best into the profession.

Parents, too, have a responsibility for their child’s education. Too many opt out – none should.

Events in California, in 1996, are suggestive. After positive discrimination had resulted in low graduation results and high drop-out rates, “Proposition 209” banned any reference to race, sex or ethnicity in University admissions.

Students were selected purely on their Grades. Admissions from Asian Americans soared. The only explanation for this was parental influence. There is a lesson here. However good teachers may be, the role of parents remains the single most important input into any child’s life opportunity.

If, as most of us accept, the economic future of the West lies, in part, with maintaining a technological advantage, we must produce the relevant skills. But we are just not doing so. China is producing over three times as many engineering, science and IT graduates as the United States. And over three times as many Chinese graduates at the top-most level with PhDs.

In the UK, in the decade to 2007, there was a fall of nearly one-third in single honours chemistry courses, and 14% in physics. The West had better focus on the fact that Asian manufacture is already moving up the value chain.

No Government is always right. Or wrong. In the UK, I applaud warmly the high ambition of Ministers in the previous Government who argued for long-term social reform. My only regret is that others, more senior and less far-sighted, sometimes over-ruled their efforts. “Thinking the unthinkable” was ditched. That was a pity.

I welcomed their early ideas – as indeed I should: many of them were my ideas long before they were theirs, and – in some cases – Margaret's before they were mine.

That doesn’t matter. In a good cause, I welcome policy kleptomania. As someone who was opening Academy Schools 20 years ago, I was genuinely delighted when Andrew Adonis developed the policy and successfully carried it forward.

Education is not our only social policy failure over decades. In our broadly prosperous country, there are still far too many graffiti-ridden slums, on soul-less Estates, in run-down areas, that dis-incentivise those who live there.

There are too many neighbourhoods where unemployment has become a way of life; where an existence on social benefits seems normal.

For too many people, self-determination has morphed into a belief in self-entitlement, where no-one is responsible for anything, and welfare is a legitimate career choice. America has problems that are similar in character.

The Coalition is now embarked on reforms to health, education and social security that are long overdue, controversial and necessary. As Labour built on Conservative policy, now Conservatives will build on Labour’s.

I hope everyone, irrespective of Party, who agrees with these reforms will support them publicly when Ministers face the inevitable protests that are to come. It will be a lost opportunity if they are sacrificed to our adversarial political system.

Within the compass of my direct experience, I have tried to look forward. I have focused on what is not working well. But I am optimistic. The Western democracies always over-estimate what they can do in the short-term and under-estimate what they can achieve in the long-term. If we accept what needs to be done – we can do it. But – as Goethe noted – “until one is committed, there is hesitancy”. We must be committed.

I would like to see a senior Minister, of Cabinet rank, given responsibility for “The Future”. His or her role would be to cast an independent eye on what needs to be done that is not being done; and what is being done that could be harmful in the future.

Such a Minister would be the voice of the next generation. The conscience of the Government. The guarantor of the legacy. To do the job well, he or she should be an enormous irritant to Departmental Ministers and the Treasury but, with the backing of a committed Prime Minister, would ensure the interests of the next generation are not sacrificed on the altar of immediate consumption.

Mr. Chairman, time is a tyrant and I have only skimmed the surface of policy for tomorrow.

I have not touched on traditional foreign policy issues – much as I wished to: that must await another occasion. On that, and on so much else, there is a great deal to be said and – as my Grace Note – let me observe that those of us gathered here are well-placed to say it.

CONCLUSION

We are, or were, the Establishment – or part of it. Some still are. We are winners in the Ovarian lottery. Gathered here are intelligent, civilised men and women, skilled at diplomacy and dispassionate judgement. If the late John Osborne were to categorise us, it would not be as “Angry Young Men or Women”, but as “Mellow Old Achievers”.

We are, many would say, the past: Neanderthals from the pre-internet age. But we have one huge advantage: we have seen the world as few others have seen it. So I want to end with a plea. It is that – in an age that glorifies youth – we should use our collective experience to help signpost a path for the future.

We may have a shorter lease on that future than the young, but they are our young, and we have an obligation to care about their future. Whether British, or American, or Continental European, the task facing our respective Governments is herculean. We can stand aside, shrug our shoulders and smile benignly on their efforts, our own work done. Or we can pitch in and help them.

That, surely, is the right thing to do.

© The Ditchley Foundation, 2011. All rights reserved. Queries concerning permission to translate or reprint should be addressed to The Editor, The Ditchley Foundation, Ditchley Park, Enstone, CHIPPING NORTON, Oxfordshire OX7 4ER, England.